Before I saw the headlines, I didn’t realize tofubeats’ latest earworm had no actual singer. The hollow voice singing about her “soul burning until it burns out” was familiar to me in the indistinct, unobtrusive way of so many guest vocalists in Japanese dance-pop, so much that it could’ve belonged to anyone. Even without a name attached to the track, I never thought for a second that this wasn’t just another ordinary girl in the studio, vocals flattened under the anonymizing force of genre-typical processing. But that girl doesn’t exist. I made her up, assumed her into being. “tofubeats to release new EP ‘without a single track featuring my own vocals,’ all songs produced using AI voice synthesis software,” articles announced two weeks ahead of its release date. The name of that EP is Nobody.

While the sales pitch might call to mind Vocaloid, so embedded in the fabric of Japanese popular culture that its flagship product just made her Coachella debut this year, the software in question is a different entity, Synthesizer V, developed by then–21-year-old University of Illinois dropout Kanru Hua in 2018. A Vocaloid must be painstakingly “broken” by its operator to sound even close to natural, but the AI component of Synthesizer V, first rolled out at the end of 2020, bypasses this hurdle, smoothing its output into an approximation of something closer to human. “I Can Feel It,” the lead single that so readily fooled me at first listen, was a holdover from tofubeats’ 2022 album Reflection, ill-suited to his own voice but an ideal guinea pig for this new technology. Speaking to the music news outlet Natalie, he joked about the thrill of programming a computerized voice to utter the word “soul” and described the tuning process as “almost like I didn’t do anything.”

It’s been twenty years since the first Vocaloids were put on the market in 2004, but soul, ironically, was their initial objective. “Virtual soul vocalists” Leon and Lola failed to make a splash among consumers: the tinny, tremulous sound inherent to Vocaloid meant that the voice banks would never see practical application for their designated purpose.1 A shift towards a colorful 2D design aesthetic made the software commercially successful in Japan for the first time, and Hatsune Miku, imagined as a 16-year-old digital idol with a “cute, deformed” appeal rather than a realistic substitute for the human voice, became a cultural phenomenon upon her release in 2007, dominating early social media platforms and launching music careers.

Given his origins in the independent net label scene, part and parcel with many of the same online subcultures that grew around Vocaloid in the 2000s, some have perceived Nobody as a return to tofubeats’ roots. That would both misread the intention behind this experiment and reframe his own musical history and ethos. “When you make a song with Hatsune Miku, it’s like you’re making that song for Hatsune Miku. You become a Vocaloid producer,” he said in a recent interview for the EP. While he’s used the software privately for demos, he’s avoided sharing that work with listeners, reluctant to “be characterized as a Vocaloid producer and lose my identity.”

I certainly watched this happen over the ensuing decade as Vocaloid “features” took on a life of their own, simultaneously building independent artists up and turning their music into what sometimes felt more like character merchandise than art. What proved to be an ace in the hole for corporate brand recognition pigeonholed the creators pulling her strings. Festivalgoers gathered in the California desert for Hatsune Miku weren’t there out of singular devotion to the many musicians who crafted her songs, but to see the blue-haired anime girl tasked with bringing them to life.

Synthesizer V has tried to position its own voice banks similarly to Vocaloid, furnishing musicians with a bountiful selection of doe-eyed teenage girls able to give their work a face as well as a voice. “Hanakuma Chifuyu,” the primary voice heard on Nobody, is described as a high school freshman with an interest in vintage cameras. But the details don’t matter here, and the characters’ lack of pop culture ubiquity makes them capable of still functioning purely as tools. He wouldn’t have used them otherwise. As a composer, tofubeats is conscious of his and the audience’s emotional transference onto a recognizable voice, human or not, shaping the music on a subjective level beyond his control. Synthesizer V, though, “has no context,” he explained. “Is there even anyone out there who could feel encouraged by these songs?”

At first, I couldn’t say I did. Like a magic trick revealed, the technological marvel of “I Can Feel It” didn’t seem to extend to the rest of the EP once I heard it, every clipped syllable and metallic echo standing out in stark relief. We’re in a collective age of creative paranoia, and a track like “Everyone Can Be a DJ” — in which a squeaky voice repeats ad nauseam what might be only a step away from the rallying cry of the terminally unimaginative, that everyone can be an artist (with the right generative tools) — exacerbates those fears to the point that its hypnotic 4/4 beat turns almost ominous. “Why Don’t You Come With Me?” is an invitation from no one to nowhere. But then the euphoria of “You-N-Me” builds until it reaches pure catharsis, a sympathetic machine reaching out to hold my hand. If you and me are together, everything will be all right. There is no “me” behind those words, but what if there is? Is it not just the music transmitting back to me the comfort it knows I need?

tofubeats’ work in this decade has tended to grapple with notions of impermanence as club culture and dance music increasingly fade from public relevance in Japan, a problem that he also brings to Nobody. Over the press cycle for the EP, he’s often referenced Towa Tei, one of the last few legacy electronic musicians still active on a major label, who just last year revealed that multiple foreign investors had attempted to buy his catalog for what he believes may have been the purpose of training artificial intelligence. Beneath the surface of these songs lie tofubeats’ own questions about technology, equality, and what makes superlative art in the shadow of one-click replication. “I think music can be a way to record the sensibilities of the times,” he said, “and for me, this might’ve been just the right theme to explore.”

I slept on tofubeats as an album artist until Reflection, a record that arrived at the exact moment I needed it. Before then he had been in my mind a kind of good-time guy, someone whose teenage beginnings I traced fondly back to my own early exploration of Japanese electronic music in the late 2000s, two children of the internet immersed in our own worlds, oceans apart. I put the album on because I was shell-shocked from an unhappy night and desperately in need of a good time, looking more for a distraction than a sincere listening experience. I can still remember the odd hunched posture I was in when I played it through for the first time, the way the songs fell distantly on my ears as good, wait, no, really good, how I sort of startled back awake at the end, the pain rushing back into the wound: We’re all carrying burdens / It’s the same for everyone / The same for everyone / The same for everyone. I love it so much I’ve never listened to any of the remixes. It might have saved me.

As a chronicle of life in the wake of significant changes and upheaval, including entering his thirties, moving to Tokyo at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, and experiencing the sudden onset of partial deafness, Reflection is a lonely, thorny, joyous album, concerned with how we define ourselves within our bodies and the space around us. “In the mirror / My invisible heart is reflected / My self that even I don’t know / Shouldn’t have existed there,” tofubeats sings in the opening track through thick layers of Auto-Tune. His voice is pitched down a semitone, just enough to be uncanny, not quite himself. In field recordings sampled from around the city, we hear two broken parking meters repeating “OK” back and forth on an infinite loop, a cosmic joke. Closer to the end, someone runs down a flight of stairs. A doorknob turns, and the door opens, in my imagination, to blinding sunlight.

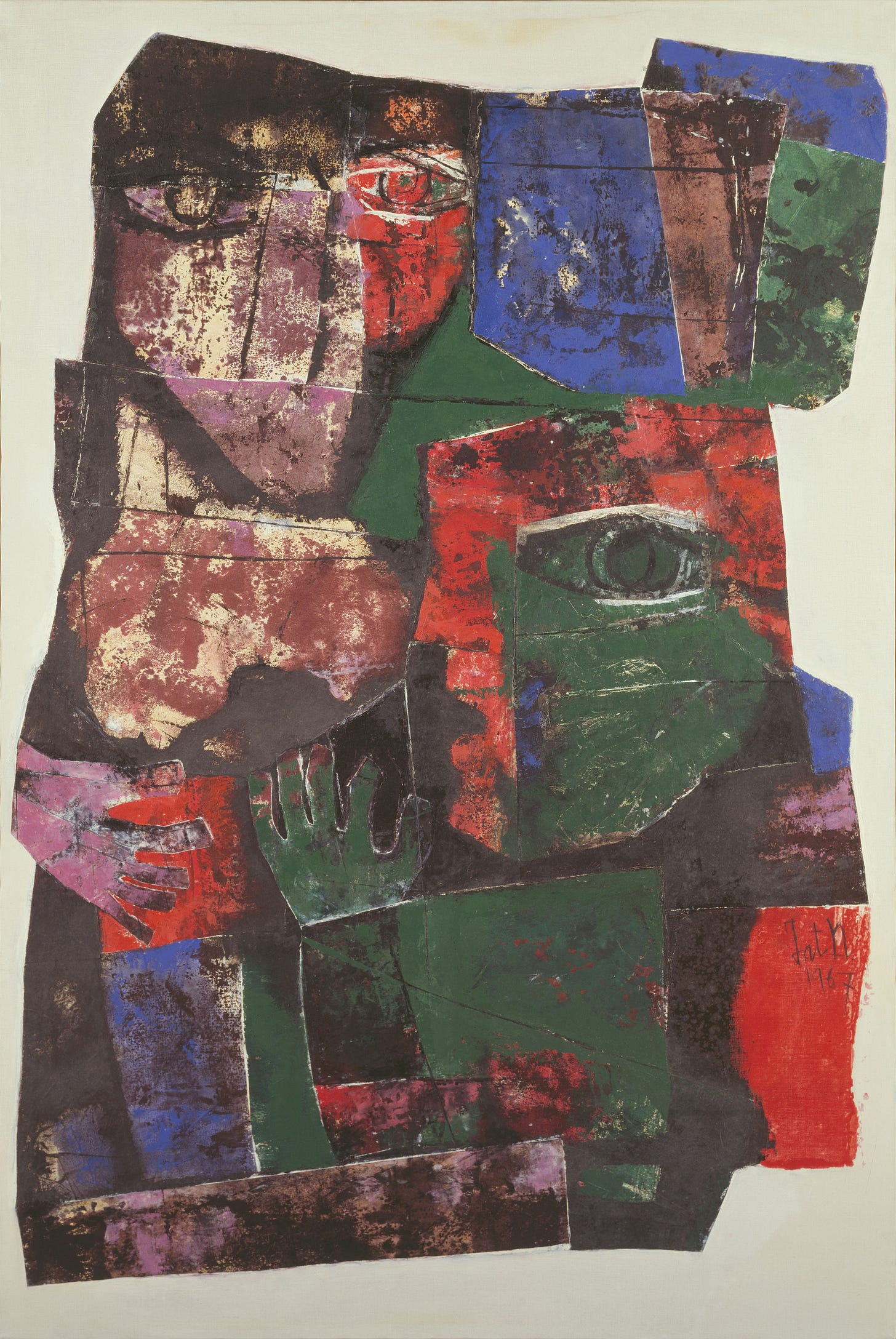

Looking back on it now, he wonders if he went too far, overshared. There’s refuge in letting the words be sounds, the voice be no one. But he’s also carried over the lessons he’s learned from other forms of art. On Reflection, the moody “Somebody Tore My P,” named for the 1943 painting “Somebody Tore My Poster,” used the Japanese-American immigrant Yasuo Kuniyoshi as a conduit for the album’s themes of alienation and belonging; this time, “Remained Wall,” Nobody’s only fully instrumental track, invokes Nakamoto Tatsuya’s 1960s Nokosareta Kabe series depicting the primal origins of humanity, an intriguing contrast to an EP so mired in the manmade.

The Yamaguchi Prefectural Art Museum provided2 the following commentary on “Altar,” one of the more famous of these works:

Nakamoto has stated that the picture is inspired by an incident that he witnessed during his stay in Italy. On a train heaving with passengers, in the heat of July, twin babies started to cry, much to the annoyance of the other passengers. The mother was clearly exasperated but she managed to placate her babies by feeding them the juice of a withered old orange that she expertly managed to squeeze to the last drop. For the artist Nakamoto, it was an unforgettable incarnation of human emotion, like the mother Mary herself, and the scene remained seared into his memory. Like a solidly built wall that remains in place for hundreds of years, the act of breastfeeding, mother to child, represents a most pristine image of humanity, one that has remained unchanged through the generations. We can assume that this inspired Nakamoto to pursue his own vision of what it is to be human.

Listening to Nobody, I can’t also help but think of Run (2018), its superficial inverse in their similar line of promotional tactics: “the first tofubeats album to be sung entirely by himself.” On some level, this was accidental — its two major singles, written for a TV drama and a movie respectively, were originally planned to feature other vocalists before the studios requested his version instead. Like Reflection after it, the album found him looking inward at himself and his place in the world, taking stock of his late-twenties disillusionment and charting a new path forward.

The bare piano ballad “Dead Wax,” while still sneakily pitch-corrected, remains the closest to untouched his voice has ever been across his decade-spanning discography, and it’s a track I keep revisiting in between the more self-evident artificiality of his latest:

The music is over

Only silence remains

My friends have gone home

There’s just me here

There’s just me here

Just me

These lyrics easily bring to mind the end of a party, a nightclub at sunrise. I think of the end of an album, though, when the music vacates the room you’re in and the air feels different afterwards. The friends here are the people in your speakers, retreating back to the void they emerged from to sing and play for you.

Meanwhile, the title track of Nobody makes me think maybe the other way around is possible, too, that music anticipates our presence as much as we reach for it. Strings played by violinist Machida Tadashi swell beneath a programmed lament:

I waited all night on the stage for you

Were you so busy that you forgot about me?

I searched aimlessly in town for you

I felt that I was just one in the crowd

Is it a sad fate to be just a tool for someone else’s creation, only real in another’s songs? She feels nothing, yet somehow I do. I think about her there in the dark, waiting for her turn to sing. But “[t]here’s nowhere for that emotion to go,” tofubeats says. “It’s literally nobody, even though the lyrics say things like ‘I kept waiting for you.’ It’s like the void is spreading. Even I thought it was crazy as I was making it.”

The closer on Run begins with the raw audio of a funny vocal warmup, a chair scraping against the floor, and the clearing of a throat before we hear tofubeats’ hands on the keys of a piano. By the end of the song, a chorus of voices joins in to sing us out in perfect, uplifting harmony. Every voice is his, all the highs and lows coming together to form the illusion of a communal everybody, strains of Auto-Tune mingling with his unfiltered vocals. It’s wholly unnatural, the unique product of recording studio trickery, no more or less real than anything on Nobody. And all the same, I feel like I want to be a part of that choir every time I hear it, our voices rising high, rejoicing in the expression of something human.

Hirasawa Susumu would later use Lola to suitably uncanny effect on his soundtrack for the 2006 film Paprika.

English translation theirs.