“The girls arrived with the recession,” opens On Gals and Quirky Girls1, Matsutani Soichiro’s 2012 history of contemporary girls’ fashion subcultures. It was the early 1990s, and the Japanese economy was in freefall, the dizzying heights of bubble-era affluence now crashing to devastating lows. Out of the rubble emerged a new breed of teen girl — hair dyed, skin tanned and school uniform skirts hiked high. These were the kogals, the school-aged little sisters of the bodycon-clad, clubgoing “gals” who danced night after night at the infamous Tokyo discotheque Juliana’s even as the world fell apart around them. Kogals, congregating in the Tokyo shopping district of Shibuya and clutching designer goods like a final lifeline to status and stability, would be among the young people to inherit Japan’s lost decades, the years of economic depression and societal malaise in the wake of the 1991 collapse.

In Think Global, Fear Local: Sex, Violence, and Anxiety in Contemporary Japan, David Leheny defines the kogal tribe as “[s]tylishly attired high school girls and young women, often with dyed hair, elaborate makeup, and provocative clothing.” An index at the back of the book categorizes them in relation to various social issues: [kogals] and morality . . . as prone to prostitution . . . as threats. “To some, the kogal represented an element of creativity and originality in a society driven too long by consumerist conformity; for others, she embodied Japan’s decisive turn toward the moral precipice,” Leheny expounds, illustrating the “hazily defined crisis” of 1990s Japan. “Crucially, as an easily recognized image, the kogal could be exploited — to sell fashion magazines, to market the need for tighter control over juveniles, or to indicate a potential direction for the empowerment of women and girls in a patriarchal society.”

Despite the bleak outlook, creativity was in the air, and kogals were only one visible example of the seismic shift about to take place in pop culture. Musically, the 1990s marked the beginning of the “J-pop” era defined by producer Komuro Tetsuya, then the foremost domestic interpreter of Western dance music trends, and the launch of Avex Trax, originally an offshoot of a music import business which would quickly establish itself as a powerhouse record label. Under Avex, this decade would see the rise of pop divas and kogal icons Amuro Namie and Hamasaki Ayumi, but before either of them, there was Furuya Hitomi, known mononymously as hitomi.

Following a brief stint as a model, 17-year-old hitomi was spotted by Komuro at an audition in 1993 and swiftly signed to Avex for further development. Her singing wasn’t particularly skilled, but prior to her debut, Komuro tasked her with keeping a diary, and upon reading it, was impressed enough to declare that she “could be the voice of [her] generation of women.” Having earned his approval, he left her lyrics in her own hands, writing the music for her songs around them and requesting that she write “not as a lyricist, but as one individual girl” expressing her own feelings.

Beginning with “Let’s Play Winter,” her 1994 debut single, hitomi would go on to write the lyrics for the vast majority of her songs, showcasing a frank and intimate personal style. “Candy Girl,” her third single and first major top 20 chart hit, exemplifies this lyrical voice: “I’m rushing through the crowd in my miniskirt again this morning / Mom says be careful of gropers . . .” The title was taken from a fashion spread she saw in Elle before her debut, featuring a model whose pose she found relatably “cheeky” and “audacious,” inspiring her to write a song about a girl who lived without a care for how others perceived her. “I can’t keep quiet / I can’t stand still,” she sings. “Sitting around like a pretty doll is much too lonely.” Komuro, who normally corrected her lyrics over the course of the writing process, connected with them from the very first draft, telling her, “No ordinary person could’ve written these lyrics.”

By the end of the decade, the kogal had evolved back into the gal, or gyaru, which began to take on a new connotation as the style continued to mutate and diversify at a breakneck pace. Dark tans got even darker, now accentuated with pale lipstick and eye makeup for contrast, and bleached hair went from brown to blonde to silver or white. These styles were flash-in-the-pan trends, a kind of reckless aesthetic extremism meant to upend traditional beauty standards, shock outsiders and quell the boredom of youth, but as W. David Marx has noted, it moved the needle of gyaru towards an “archetypal working class delinquent subculture” a world apart from its quiet luxury origins. In the years to come, gyaru would be commodified to the point of amorphousness, spawning an infinite number of permutations from the softer, mainstreamed looks of Popteen magazine to the cultural appropriation chic of B-kei, a style derived from the imitation of Black fashion and music cultures.

Enter the 2010s, and enter mini. Captivated by the stage after seeing her first musical at the age of five, mini dreamed of a future in theater, a thorn in the side of her stereotypical kyouiku mama mother, who prioritized her placement in a good private school and saw no value in the arts. By the time she made it to high school, she was auditioning and performing weekly at local clubs with no lucky break in sight.

“When I was in high school, I was really wild and nothing I wanted to do went right,” she wrote in a series of blog posts about her life. “All the adults around me kept telling me to ‘be normal’ and it felt like my self was being erased before my eyes, and every day, I honestly thought that if this world was such a worthless place, then I wanted to die.” Singing felt to her like the only way she could externalize her identity; as she continued to struggle to pursue dream into her twenties, she longed to reach and reassure others who felt as hopeless as she did through her music.

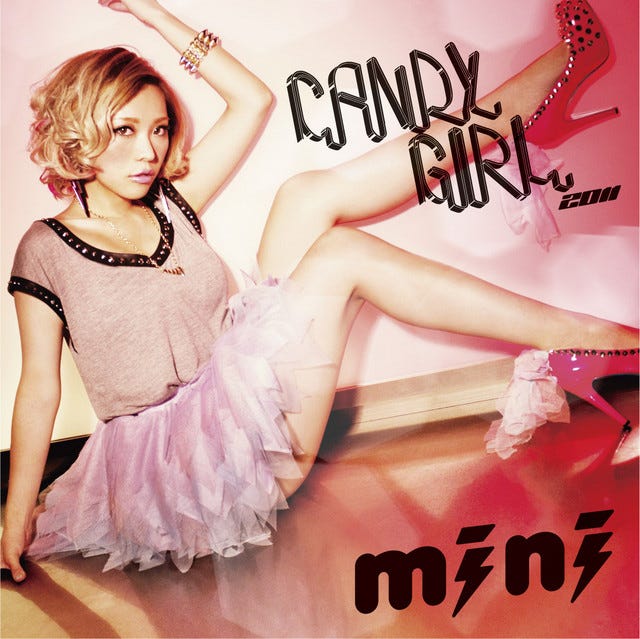

A self-confessed “B-gyaru” in her early years, she found a way into the entertainment industry through modeling for gyaru magazines, and in 2007, at 22, she launched her own small-scale modeling agency between writing lyrics and singing backup for popular artists like GReeeeN. Jin, their producer, eventually helmed the direction of her major label debut through Avex in 2010, and a rush of buzzy articles went to press about the hot new up-and-comer. Every pop girl needs an outlandish selling point, so mini’s became her legs, which the media breathlessly reported were insured for 100 million yen. When she finally made her way onto music shows, models from her agency occasionally flanked her in the role of backup dancers and squad members.

It was the peak of the electropop boom spurred by girl group Perfume’s breakthrough success at the end of the 2000s, and mini had the best foot in the door of this scene that any new singer could ask for: a remix of her debut single, “Are U Ready?”, courtesy of none other than Nakata Yasutaka himself. It likely came as a favor to nishi-ken, the producer who would mold her edgy, dubstep-tinged sound, and, by no small coincidence, a childhood friend of Nakata from his hometown of Kanazawa. Written by mini, the aggressive chorus is like the fight song she’d wished could touch others who shared her same pain so many years ago: “I can’t see the answer / If you say that / Then you can make an answer of your own / I believe in myself.”

But still no hit. After two singles, a digital release here and a collaboration there, none of which did significant numbers, the 2011 earthquake hit and put a halt to her already uncertain future. Still, if there’s one benefit to signing with Avex, it’s that they’re home to some of the most enduring pop classics in modern Japanese music history, and when desperation strikes, the catalog is always open. “My staff had the idea that I could try remaking one of [your] songs,” she revealed in an interview with hitomi. “They said there might be something in common between us, and my whole team got really excited about it.” Approaching the track as a rework rather than a cover, mini furnished the song with new verses from her own point of view.

It’d be hard to ever go wrong with that iconic opening riff, but nishi-ken gives it the drawn-out entrance it deserves, taking hitomi’s beachy, breezy original and shrouding it in fog thick enough to anticipate the proud silhouette of a diva. When it finally hits, the rush is exhilarating. Where hitomi is all easy, lighthearted, unbothered cool, there’s a clear defiance to mini’s rewritten verses, a snarl at the edge of every consonant. This is a matter of life and death, they say, and the self is the site of the bloodshed. Seeing a man’s “sour face” turned in her direction on the subway, she shoots back:

I ignore him and put on my sunglasses

On my headphones, I play music

Runway, click-clack, catwalk

'Cause there’s someplace I’m headed

“When I was given this song to remake, I took myself back to how I felt in middle and high school and decided to write about what I saw around me in those days,” mini explained her thought process. “On the subway, there’d be old men and office ladies who judged us for spending our time doing the same thing every day, and us girls would look sideways back at them like, ‘That’s none of your business. I’m going to follow my own path,’ our heels clicking as we walked on ahead.”

“Being the same as someone else / Doesn’t that just make you an android!?” she spits with the same venom for conformity and authority, the cages she sought to escape since her adolescence. “There’s only one of me / So I’m going my way with no fear.” In many ways, it’s an overt love letter to the brash, fiercely individualistic gyaru ethos and community that helped her find her footing when she was at her lowest. Filmed on location in Shibuya 109, the holy mecca of gyarudom, the music video is rife with Easter eggs — like a shot of the gyaru favorite blog platform Crooz open on an extra’s phone — that you’d only recognize if you were very clued in to Japanese youth fashion in the new millennium, or lived it. Yet in another way, it’s a message in a bottle, carried to shore for those who need it. “I tackled the lyrics with the idea of them being a message to all the candy girls,” she said in the same interview. “I hoped that the answers I discovered for myself while taking so many zigzagging detours over the course of my life could serve as some kind of hint to teen girls now.”

Released in 2012, mini’s debut full-length album, the cryptically titled Electro Hardcore Bang Bang Picasso, also became her last. I’ll never not find this a shame. The songs are biting and sassy — relentless, full-throttle dance pop, pushing the limit so far that you can picture the giddy, punch-drunk thrill in the studio where they were produced. Whether or not they’ve necessarily aged well is besides the point; the point is that they fully captured the moment they were made in, down to something as silly as a RoxXxan-sampling bridge, and introduced to that moment a capable voice who deserved another chance to be heard. (And on a more subjective level, the Britney-aping “Pray” wears its self-made artificiality so well that I’m surprised it has yet to be discovered by the newer generation of popheads.) Following the release of Picasso, a free sampler was distributed in Tower Records stores containing an unfinished demo known only as “Crazy Stripper,” an absolute 10/10, “Technologic”-but-make-it-cunty banger of a track that every true J-electro veteran still mourns. Legend has it that you can hear it playing from someone’s abandoned Tumblr to this day.

Here in the 2020s, I can’t help but feel that, conceptually, the outrageous, larger-than-life Japanese pop star is dead. Gyaru may outlive me yet, but as mass culture steadily erodes from the public sphere and leaves only wreckage behind, mini will remain in my memory as one of the last manufactured icons of a fading subculture.

But after a decade away from the spotlight, she’s now the mother of a young daughter, surely teaching her the lessons she hoped to share with the candy girls of the world. For the time being, here’s one from mini and hitomi to you:

Anyone can fly away from zero

The possibilities are limitless

In order to reach that shining something

I guess I have to be the one to change, right?

『ギャルと不思議ちゃん論―女の子たちの三十年戦争』 (Gyaru to fushigi-chan ron: onna no ko-tachi no sanjuunen sensou)